A narrow lane abutting Sri Guru Singh Sabha, the largest gurdwara in Bengaluru, located on the periphery of Ulsoor Lake in central Bengaluru, leads to a dense warren of bylanes which are collectively known as M.V. Garden. In one of these minuscule bylanes, in mid-May, a knot of women surrounded Munishame Gowda holding aloft their Aadhaar cards, ration cards, and Scheduled Caste certificates. Gowda, a schoolteacher, is an official enumerator appointed by the Justice (Retired) H.N. Nagamohan Das Commission, which has been constituted to conduct a Comprehensive Survey of Scheduled Castes in Karnataka.

A woman named Shabila waited patiently as Gowda keyed in crucial identification details about her on a specially designed app on his mobile phone. Before proceeding with recording the socio-economic data of her family based on 42 separate parameters, he asked Shabila for the OTP (one-time password) that should have come as an SMS on her phone. Everyone waited for the OTP; the women, calmly, and Gowda, frustratedly. “I have visited 28 households since the morning. It is easy to verify identity information with the ration cards but in some cases, the Aadhaar card is not linked to the ration card and this is causing a lot of problems.” The OTP finally came and Gowda entered this into the app before commencing his questions: “Caste?” “Scheduled Caste Adi Dravida,” Shabila responded. “Sub-caste?”: “I don’t know.”

After this, a list of questions followed: members of household, marital status, education, income, occupation (organised/unorganised sector), government job if any, benefits obtained from reservation, political representation, type of residence, agricultural land, vehicles owned and similar questions with the final query being “Is your household subjected to any social discrimination stigma?” After running through this list for around 20 minutes, Gowda took a picture of Shabila’s signature and submitted the form on the app on his mobile phone. With this household done, Gowda moved on to the next woman who was waiting for her turn and began to ask her the same set of questions.

Gowda is one of the 59,000 enumerators enlisted for the mammoth survey being undertaken by the Government of Karnataka to cover the approximately 25 lakh Dalit households in the State. The survey is being done in three phases: in the first phase, which began on May 5 and will go on till May 25, all Dalit households in Karnataka will be visited. Special camps would be held in the second phase between May 26 and 28 and in the final phase between May 19 and 28; an online self-declaration option would be provided to respondents. The aim of the Commission in conducting this comprehensive survey is to use this empirical data to recommend a policy of internal reservation among Dalits in Karnataka.

Also Read | Caste census: A powerful tool to reimagine the nation

The Nagamohan Das Commission was constituted by the Karnataka government in November last year following the landmark Supreme Court judgement of August 1, 2024, which upheld the Constitutional validity of States to provide internal reservation (subclassification of different castes) for Dalits in education and government employment under the broader Scheduled Caste reservation quota. Interestingly, this judgement (State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh), was delivered by a seven-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud after considering the contrarian judgements of two five-judge benches of the Supreme Court: In 2004, a five-judge bench had disallowed subclassification, while, in 2020, a five-judge bench had allowed subclassification. Thus, the matter was adjudicated by this seven-judge bench, which also emphasised that subclassification must be done based on “quantifiable and demonstrable data by the States which cannot act on its whims.”

Dalits in Karnataka

There are 101 Dalit castes in Karnataka. Numerically, most of the Dalit castes in Karnataka are divided into two broad agglomerations: the Madigas (or the left-hand Dalits, consisting of 30 castes) and the Holeyas (or the right-hand Dalits, consisting of 25 castes), both of which were deemed “untouchable” castes historically. While the Madigas worked with leather and its byproducts, the Holeyas were agricultural labourers. Apart from this, there are also “touchable” Dalit castes such as the Lambani, Bhovi, etc., which are lesser in number when compared to these two large clusters.

Since the 1990s, Madigas have been demanding that internal reservation be implemented in Karnataka as they alleged that the benefits of reservation policies were disproportionately gobbled up by the Holeyas, thus depriving them of equitable benefits. Responding to this clamour, a Commission was appointed in 2004, headed by Justice AJ Sadashiva, which studied the issue and submitted its report in 2012.

Although the report never saw the light of day because of its immense socio-political implications, leaked copies sharply confirmed the sense that Madigas were relatively more backward than the Holeyas and the “touchable” Schedule Castes, even though they were more in number. It is widely acknowledged by political observers in Karnataka that it was Siddaramaiah’s (who was Chief Minister at the time) dithering on formally accepting the Justice Sadashiva Commission report that was a contributing factor leading to the defeat of the Congress in the 2018 election, as Madigas abandoned the party and endorsed the BJP.

In 2022, the then BJP government entrusted Law Minister J.C. Madhuswamy to submit a report on subclassification of Dalits based on which Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai hastily implemented a policy of internal reservation but this was merely a red herring as, since the matter was slated to come up before the seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court, it could not be implemented.

When there is a Commission’s report available already (i.e., Sadashiva Commission report), what was the need for another Commission to gather the same data? Speaking to Frontline, Justice Nagamohan Das answered this question, “In the 2011 Census of India, the Scheduled Caste population of Karnataka was stated to be around 104 lakhs, but in Justice Sadashiva’s survey, which was conducted within a few months of the Census, this number came down to around 96 lakhs. Among the respondents in the Justice Sadashiva survey, 23 per cent listed their caste as Adi Karnataka, Adi Dravida, or Adi Andhra. Each of these is not a separate caste but a group of castes. Respondents can either belong to the Holeya or Madiga grouping, so without knowing the subcaste, it is not possible to devise a policy of internal reservation.” (Even the 2011 Census of India recorded that 43 per cent of the Scheduled Castes in Karnataka identified as Adi Karnataka, Adi Dravida or Adi Andhra).

The knotty conundrum to which specific subcaste Dalits, who state their caste as Adi Karnataka, Adi Andhra, or Adi Dravida, belong to has its provenance in a decision taken more than 100 years ago in 1921. According to Justice Nagamohan Das, a government notification was issued in the princely state of Mysore whereby all members of the “Depressed Classes” had to record their caste as one among these three.

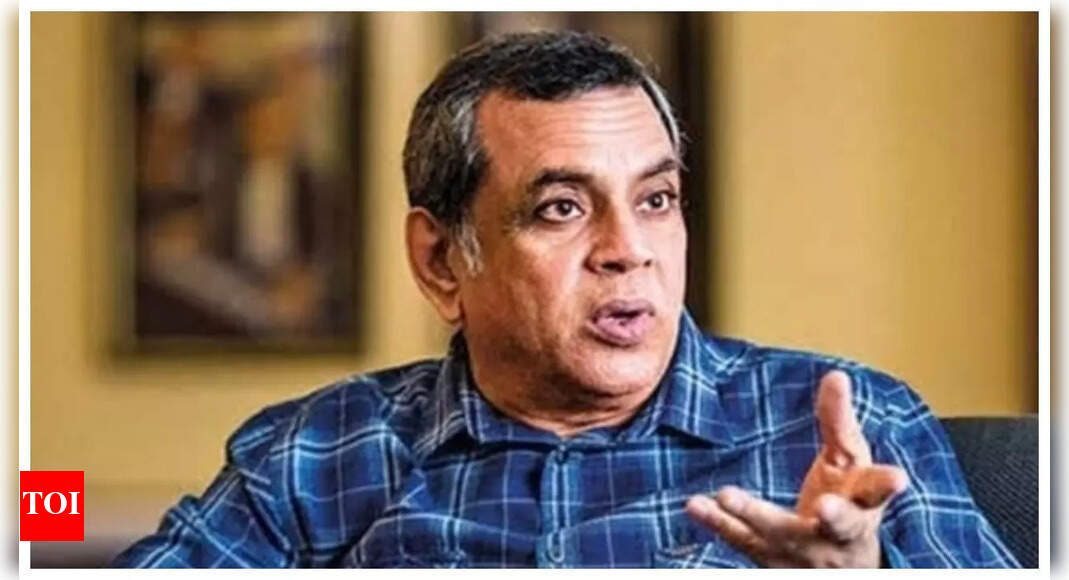

Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah receives the interim report of the committee headed by retired Justice Nagamohan Das, which was formed to provide internal reservation for Dalit communities, in Bengaluru.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU

“Kannada-speaking Dalits came to be known as Adi Karnataka, and similarly, Tamil and Telugu-speaking Dalits began to refer to themselves as Adi Dravida and Adi Andhra, respectively. There was a huge migration to Mysore from neighbouring territories because of which it was difficult to extend benefits to migrants and locals based on their social status, so this notification was issued,” he explained. The Social Welfare Ministry has also issued several advertisements in newspapers advising respondents to list their subcaste if they belong to these three specific linguistic Dalit groupings.

According to Justice Nagamohan Das, respondents are aware of their subcaste but do not acknowledge it publicly. This information regarding a Dalit’s specific subcaste is also easy to verify in a rural milieu where caste identity is public knowledge but in urban areas (as Shabila’s case showed) the ignorance may not be a pretence. It is unclear how the Justice Nagamohandas Commission will wade through this hurdle as it will be difficult to accurately quantify the tally of Holeyas and Madigas in Karnataka without resolving this quandary. Data collection is also representing a significant challenge in Bengaluru where enumerators have complained that apartment complexes were not allowing them inside for the survey.

Justice Nagamohan Das added that ascertaining accurate numbers of each Dalit caste was the first step but a recommendation could not be as simple as apportioning reservation based just on demographic data, so a further, detailed dataset on social, economic and political indices was also being gathered so that internal reservation could be provided based on a caste’s relative backwardness when compared to other Dalit castes. “There are some Dalit castes who have many Group A officers, but certain other Dalit castes do not even have an attender (a Group D job) among them. We should ensure that everyone gets representation,” he added.

Questions have been raised, though, on the hasty way through which a survey of this magnitude is being undertaken. Indudhara Honnapura, senior journalist and one of the founder members of the Dalit Sangharsha Samiti in Karnataka, said, “The survey should be perfect but a few days is insufficient to do this. Of the 101 Dalit castes in Karnataka, 51 are nomadic, semi-nomadic and denotified castes. Among these, many are microscopic communities that do not have address proof, voter identification, they have no land and are constantly on the move. How will they be surveyed?” Members of the Commission have also acknowledged the significance of this problem although it is unclear how information of persons belonging to these migratory communities is being gathered.

In a public note issued on May 19, Social Justice Minister Dr. H.C. Mahadevappa stated that “Once the survey period is completed, the Commission will incorporate information about Scheduled Castes who have been left out of the survey and will also correct any mistakes in the information gathered.”

Honnapura also hoped that the Nagamohan Das Commission’s recommendations for reservation would go beyond education and government employment and extend into the political realm because “none of the smaller marginalised Dalit communities have attained political representation.” Honnapura’s point about political representation stems from a real concern, as all 36 Scheduled Caste MLAs in the current Karnataka Legislative Assembly belong only to four Dalit castes or agglomerations: Holeyas (14), Madigas (8), Lambanis (7) or Bhovis (7). There are no MLAs from other, smaller Dalit castes. This figure also shows that the cluster of Madigas, who, by popular reckoning, constitute the largest number of Dalits in Karnataka, have fewer MLAs when compared to the Holeyas.

Also Read | Will Karnataka’s caste survey unlock a new era of political equities?

Concerns have also been raised on how certain non-Dalit communities are attempting to enlist as Dalit castes in the survey. In two letters to Justice Nagamoha Das on May 13 and 15 respectively, Food and Civil Supplies Minister K.H. Muniyappa cautioned the Commission that Lingayat Jangamas (a non-Dalit caste) were trying to list themselves as Beda/Budla Jangamas (a Dalit caste) in north Karnataka and that some members of the Mogaveera caste (a backward caste) in coastal Karnataka were attempting to list themselves as members of the Moger caste (a Dalit caste).

Throughout history, the census, or surveys of that nature, have led to profound reconfigurations of sociological identity of vast groups of individuals. Studies on the history of the census in India from its colonial origins in 1871, and in its decennial iterations since then, have shown how nebulous identities have elided leading to the creation of homogenous monoliths.

While lacking the grand scale and cachet of a census, the ongoing survey in Karnataka has also led to caste groups and associations using traditional and social media to spread their message with Holeya and Madiga associations and leaders taking the lead. In their advisories, they strongly recommend that only prescribed caste names must be provided to survey enumerators. Such advertisements have been legion in Kannada newspapers over the past few weeks with the officially endorsed caste names helpfully listed to make the process straightforward. Consolidating and bolstering their numbers seems to be important for the leaders and political representatives of both these agglomerations as it could potentially lead to advantages when the matrix of internal reservation is finally recommended, and, subsequently implemented.

This development made a senior Dalit leader, who has closely observed the trajectory of the Dalit movement in Karnataka, lament, as he saw this as a step back for the Dalit movement, which in the early decades since its founding in 1974, even transcended its caste moorings with its progressive worldview. “Holeyas and Madigas are fighting among themselves to ensure that they secure the benefits of reservation while ignoring smaller communities. Internal reservations for Dalits is the need of the hour but it could have been done unanimously by all Dalit communities. My pain is that the dominant Dalit communities did not support this justified demand.”