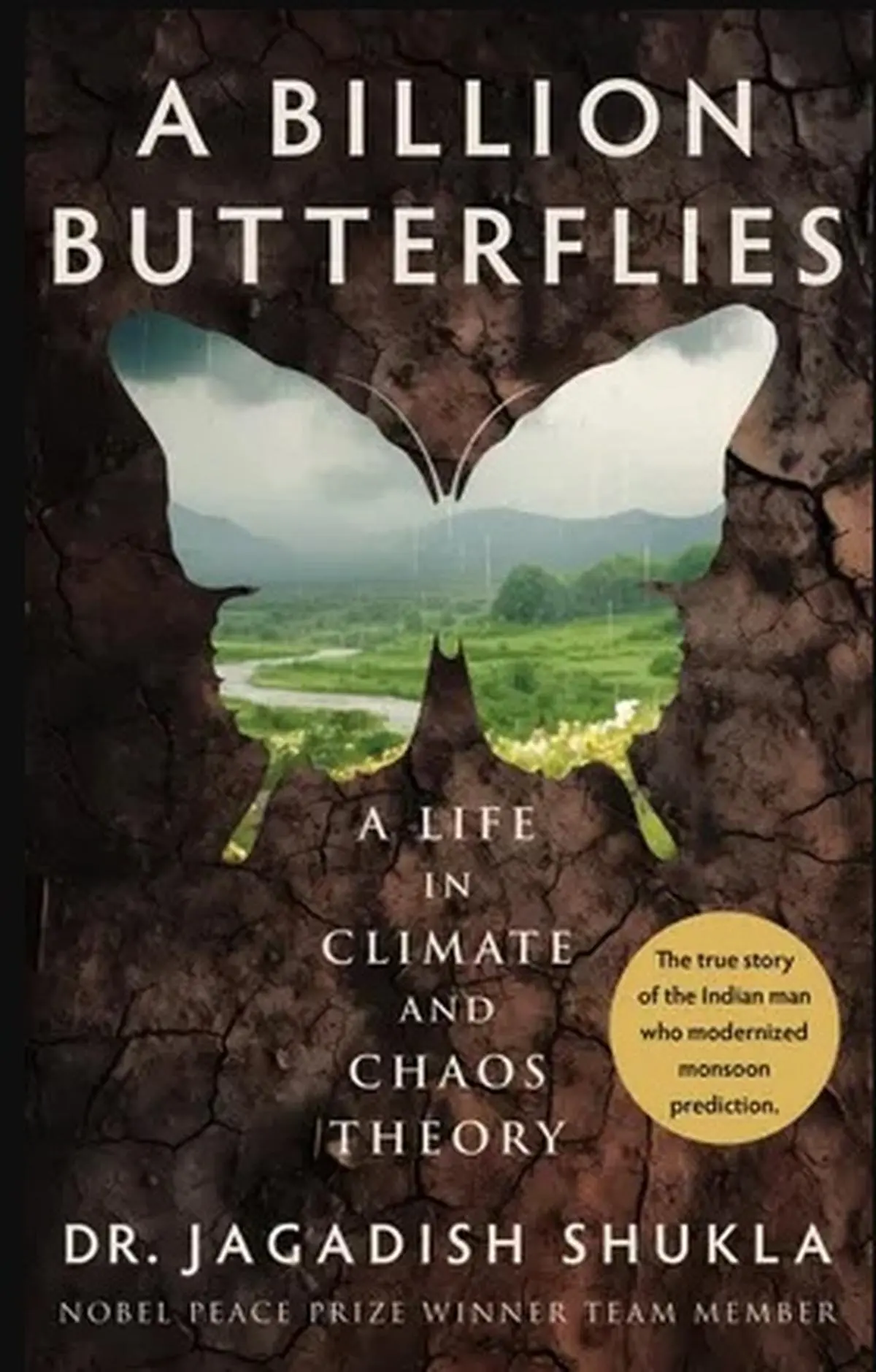

Jagadish Shukla, meteorologist and author of A Billion Butterflies: A Life in Climate and Chaos Theory .

| Photo Credit: By Special Arrangement

Predicting tropical weather is an exacting but necessary science. The eminent meteorologist Dr Jagadish Shukla, whose book A Billion Butterflies: A Life in Climate and Chaos Theory is scheduled to be released on May 24, has devoted a lifetime to improving accuracy in seasonal weather predictions, and monsoonal predictions for India in particular. Dr Shukla spoke to Frontline about A Billion Butterflies, which in many ways is a memoir as well as a book about weather and climate science, his personal and professional journey, and his assessment of the state of science education and weather prediction today. Edited excerpts:

What prompted you to write the book?

I have three grandchildren who were born in the United States. They will never know about my village. I wanted to tell them my story. The second reason is that a lot of American professors who come to visit my village kept asking me to write my story. What struck them was that I was born in a very backward area with no roads, no water supply, no lights and only kerosene lamps and then I went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). But the deeper reason is that I really wanted all the kids in villages like mine and in my family to know that they should not lose hope. That it’s possible to achieve what one wants if one keeps a focus. The work on monsoon prediction shows this.

Also Read | India’s environmental pioneers: The forgotten story

From very early on, you wanted to understand the “why” of weather. And seasonal predictions, especially monsoon predictions for India became a singular focus for which you even turned down other jobs and opportunities. Could you explain why?

I come from a village in Uttar Pradesh where there are many poor people. And every time there was a monsoon drought, there was a lot of suffering in the village. Many families were much poorer than us. And a lesson I learnt from my mother was to help other people who are not as privileged as we were. I started thinking what I can do for my village.

I came to the United States to understand the weather better. You cannot predict unless you understand. These days people will say you can predict with machine learning and you don’t really need to understand. Anyway, that’s a different matter. I wanted to understand why.

Some scientists had asked me to work on global warming and I said no. My main motivation was to help my village by producing better monsoon forecasts. In the village, the only experience I had with the climate was monsoon droughts. And it affects everything… agriculture and planning for water use.

Life takes some complicated turns because when I went to MIT, I met the guru of the butterfly effect, Edward Lorenz, who was a professor there. I did not know him because my background at that time was not deep in meteorology. And he was saying the weather cannot be predicted beyond 10 days. So, I started working on the problem. I found that OK, maybe the weather cannot be predicted but the seasonal mean (average) can be predicted. And I wrote a paper titled “Predictability in the midst of chaos”. This is where the title of the book also comes from.

Could you explain “chaos theory” and “butterfly effect” for a general audience?

The name “butterfly effect” came from Lorenz. He took simple equations and changed the initial conditions very slightly. The effect was as small as the fluttering of the wings of a butterfly. He showed that the outcome was very different.

The butterfly effect says that we cannot predict the weather beyond ten days. I wanted to know if there are circumstances where even a billion butterflies do not make a difference…when we change initial conditions completely like taking two different years and checking if the seasonal mean changes.

I conducted the billion butterflies experiment to show that predicting the seasonal mean is possible. I took two different years, i.e. two very different initial conditions where ocean temperatures which are scientifically called boundary conditions where the same. So, if ocean boundary conditions are the same, even the effects of a billion butterflies disappears because the seasonal mean rainfall remained the same. This showed that the seasonal mean was predictable. It was a very complex model… very non-linear. But still the results converged to identical seasonal mean rainfall.

A Billion Butterflies: A Life in Climate and Chaos Theory

By Jagadish Shukla

Macmillan

Pages: 284

Price: Rs.750

How would you assess the state of seasonal predictions today, both in India and at the world stage?

Seasonal predictions today are based on dynamical models around the world. But for the longest time, India kept using statistical models. For statistical modelling, you simply take past data, find correlations and use these correlations to predict the future. Like “this happened in March, and so this will happen in July”. In modern weather prediction, we solve billions of such mathematical equations on a super computer. It is very complicated and cannot be solved without a super computer. It is also called numerical weather prediction (NWP).

In the past, statical methods were what we had. A physicist called Gilbert Walker started this in India in 1924. There were no better methods. But even when weather prediction was modernised, India was not using it. And the most inappropriate and incorrect statistical models were used. They kept predicting a normal monsoon which was fine for some years but then suddenly in 2002 we had a massive drought.

During Rajiv Gandhi’s prime ministership, he got President [Ronald] Reagan’s permission to get a supercomputer to India and I was asked to set up a NWP centre. This modernised the whole weather prediction system in India. Today, we have the National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting under the Ministry of Earth Sciences. But even now if you go and ask people in New Delhi how they make seasonal predictions, they will say they combine statistical and dynamical models. We can get some guidance from statistical models but more and more, I see dynamical models being used. The challenge today, globally, is to improve seasonal predictions.

Why do you say dynamical models are better than statistical?

Dynamical models are better because they are based on the fundamental laws of physics like how air moves from one point to another, how temperature changes… it is very advanced science. We use Newton’s law of motion, laws of thermodynamics and these are based on mathematical equations.

What do you think about the state of science education in India today?

The very first page of the first chapter in my book shows the state of science education all over the world. The students in my university [George Mason] did not know why it gets cold at night. They knew only half the answer. I would urge everyone to read this. And I brought this up to make a point about science education. Lack of awareness about fundamental science leads to problems like people being skeptical whether climate change is real or not.

In India, science education is very different in different places. We have some great institutions in some places. You are based in Bangalore. Science institutions working in every possible area are in Bangalore. But we don’t have many science institutions in Uttar Pradesh. Someone can say it’s because people in Uttar Pradesh are not smart. But building science institutions requires development. So, good institutions are getting better and better. This is true in the United States too. Harvard, MIT, and Princeton keep getting more and more grants because they attract a lot of students. It’s a feedback effect. We need a major national effort to bring up science education throughout India.

The state of science education in villages is very poor. I find it difficult to get science teachers for the college I started in my village. We don’t have science classes because we can’t get teachers who understand science. In India, we have successful programmes like our space programme and nuclear programme. But fundamental sciences are not as advanced except in a few institutions.

Under the Modi government, do you see politics interfering adversely in the functioning of scientific institutions in India? I ask this because a recent news article about scientists at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology in Pune studying the impacts of havan [fire rituals] on aerosols and rainfall caught my attention.

It is a rubbish experiment to relate havans and rainfall. Clearly, someone has an agenda to show and to interject religion into science. What is the difference between a havan and other fires which emit particulate matter? There are so many fires [like waste burning] which can be studied without spending a lot of money. Also, for it to affect rainfall, the scale has to be massive. Like fires in the Amazon forest. And the relationship between particular matter and condensation is complicated. The people who are doing this study might get mad at me for saying this but it’s not a scientific project. And the media has a role to play here to highlight the facts.

Coming to climate change, if you were starting today would you have picked climate as your field of study instead of seasonal predictions?

Climate change is now a question of policy about how we cut emissions and how we adapt. Because we already know the science of climate change. I keep arguing with people in the United States that we are using so much computer time and so many people to show that climate change is real and temperatures will increase in more and more detail. We could be using the same resources on seasonal predictions which directly affect people’s lives. So, the answer is no. Even today, I would still focus all my projects on seasonal predictions.

Also Read | Ancient magic in Auroville: A tiny forest holds hope for the future

In the book, you mention that reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) keep saying the same thing over and over again. And you also write that climate modelling groups tend to prioritise submitting their results to the IPCC rather than focussing on improving their models. Could you elaborate a little more on this issue?

Yes, IPCC reports keep repeating the same thing again and again. In the US, we have two big centres: one in Princeton called Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and the other in Boulder called National Center for Atmospheric Research. I tell them that instead of submitting their results every five years, they can submit every ten years after working to make their models better. I guess everyone feels like if they don’t submit, they’re not a part of the party.

We should also study why different models are giving different results. This will improve the confidence in model predictions. The confidence is even less for regional predictions. For example, some results show that rainfall for India will increase, but in which parts of the country will it increase?

Finally, there is a big debate brewing within the scientific community about whether scientists should engage in activism and climate activism in particular. In your book, I saw you move quite seamlessly between science and then activism like writing letters and engaging with political leaders both in India and the United States. How do you see this debate about scientists engaging in activism?

There are people who say “stick to the science”. I don’t believe this. I teach undergraduates and I tell them that the solution to climate anxiety is climate action. I strongly believe this and everyone may not agree with it.

Rishika Pardikar is an environment reporter based in Bengaluru who covers science, law, and policy.